There are a few cricketers who have found their niche since the day they held the bat or ball for the first time. However, some cricketers are so talented (or not) that they played a completely different role than what they started off with when twilight dawned on their illustrious careers. Let us have a look at a few of the latter; you may be surprised by some of the role reversals they've gone through!NOTE: It is commonly believed that Sanath Jayasuriya was selected in the Sri Lankan team primarily as a spinner and then made it through the ranks as an aggressive opening batsman. However, this is far from the truth. Jayasuriya started his career as a lower-order batsman who was seen to be moderately adept at rolling his arm over in the sub-continent, but never as a specialist bowler who could bat. The fact that he bowled 9 overs in his first 10 ODIs and just one spell of 6 overs in his first 6 Tests, with most of these matches away from the subcontinent, is testament to this fact.

#1 Asif Iqbal

Many of you might consider and remember Asif Iqbal as a bowler. And indeed, he made his first impression as one. But coming to bat at No. 10 in his first ever innings, he stroked a well-composed 41 and was immediately rewarded with a shot at one drop by legendary batsman Hanif Mohammed. Though he scored a fine 36, he was back to batting below the keeper at No. 7 and 8, occasionally even 9.

His big break came in the third Test on the tour to England in 1967, when he came into bat at 7-53 which soon became 8-65. An innings defeat loomed large, but where the whole team faltered, Iqbal stood tall among the ruins and stroked his way to a sublime 146.

Things took a U-Turn from then on. Iqbal turned from a pure new-ball bowler to a bowling all-rounder to a batting all-rounder. By the time he was done, he was a pure batsman who did not bowl at all (more specifically he did not bring in himself to bowl as captain). His bowling credentials were nowhere near bad, he finished with over 50 wickets at under 30-a-piece. However, he had 11 hundreds and 12 fifties, all when the going was tough at No.5 or 6 and lead the team to many victories and draws.

He played merely 10 ODIs and astonishingly scored 5 fifties, a ratio of 1 in 2 matches. He did come on to bowl in the shorter formats, though, and had 16 scalps at 23.82. Of course, he did not bowl with the new ball – Sarfaraz Nawaz and Imran Khan had formed one of the most formidable opening pair by then.

#2 Scott Styris

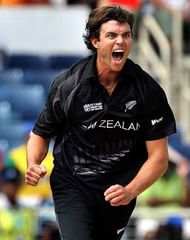

Scott Styris made his debut as a specialist seamer and batted down at numbers 6-10 for more a year and a half since debut. However, when Zimbabwe came visiting in early 2001, Styris smoked a brilliant six which was enough to prompt Fleming to promote Styris to number 3 in the next game after a 153-run opening stand.

Sent in to accelerate, Styris did exactly what was required to remain unbeaten on 48 in merely 33 balls, quite heavenly back in the early 2000s.

A freakish knee injury meant he had to concentrate more on his batting to retain his place in the side and soon a bowler who could bat became a batsman who would occasionally come on to bowl. Styris eventually finished his career after the 2011 World Cup with 9 international centuries and 35 half-centuries across all formats, averaging 36.04, 32.48 and 21.40 in descending order of longevity of the format along with a stunning performance in the 2007 World Cup.

His Test and ODI bowling averages of 50.75 and 35.32 provide compelling evidence of the transition.

#3 Ravi Shastri

A story quite similar to Asif Iqbal. Though his vocabulary may be restricted to a few cliches, his cricket certainly wasn’t.

Ravi Shastri debuted for India as a genuine off-spinner batting at number 10 in both innings. His scores of 3* and 19 were hardly a premonition of things to come later. In his 2nd Test, Shastri scored a gritty 12* defying the New Zealand bowlers for close to a 100 minutes. He was rewarded immediately with a promotion to number 5 ahead of the likes of Syed Kirmani and Kapil Dev, but his score of 5 meant he slid back to number 9 in the second essay.

Meanwhile, his bowling, the primary reason of his selection was going great guns as he finished with 7 wickets on a lifeless Auckland pitch in that match. Back home in his second series against England, he slid back to number 10 and flattered to deceive with another single digit score. However, Gavaskar still rewarded him with a go at number 6 and Shastri finally showed why – his patient 33 of 134 balls was the third-highest score on a viciously turning pitch.

His ups and downs in the order continued thick and fast even after making a spectacular 93 coming to bat at 237-6, more than 200 runs adrift of England’s first innings total.

The 1st Test match at Lord’s saw regular opener and captain Gavaskar open with debutant Ghulam Parkar. Parkar’s scores of 6 and 1 meant it was the only Test he played in his career.

Dropping Ghulam meant a selection headache for the openers spot. Vengsarkar, Vishwanath and Yashpal Sharma were vital cogs in the middle-order. Sandeep Patil, dropped after a string of poor scores when England came to India was certain to replace Ashok Malhotra in the middle-order.

Instead of a like for like replacement, Gavaskar did the unthinkable – he decided to open with Shastri and bought in the medium/leg break bowler Suru Nayak in the side.

The decision faced much ridicule as Shastri promptly returned the favour with a 7-ball duck. And 1 wicket in 2 matches meant time was of the essence for the youngster. However, he showed glimpses of what was to come opening the batting (may or may not have had happened if Gavaskar was not injured himself, though the team selection strongly indicated he would), by stroking a sublime half-century at the Oval.

Back in the sub-continent for the next series, Shastri was down to 8 again in the first Test at Karachi against Pakistan. Scoring 7 and more importantly 0 wickets in the match meant the rope had run out for him.

However, that possibly was the blessing in disguise he desperately needed. In the 6th and final match of the series, Ravi opened the innings again and turned on the heat with a patient 128 spread over almost 500 minutes.

Gavaskar continued the surprises as he decided not to expose Shastri to Holding, Roberts, Garner and Marshall when the Indians toured the West Indies in 1983, instead opening with a more regular and gritty one – Anshuman Gaekwad.

However, in ODIs he was thrust to the top in the 2nd ODI in the same series and scored 30, his highest to that point after failing again as a batsman in his next match.

The 1983 World Cup followed and he bizarrely batted in the following sequence: 10, 5, 1, 2 and 8 and the group match against Zimbabwe turned out to be his last contribution in the World Cup. He had a decent run with the ball, however, could not get a single score over 20 with the bat.

Finally, he smashed his first century in the ODI series against Australia in the 5th ODI at the top of the order but still wasn’t a given as an opener. However come the World Championship in 1985, Shastri scored a hat-trick of centuries and more or less cemented his place as an opener since then.

Interestingly, Gavaskar and Kapil Dev had quite a stark difference in opinion on this. When Gavaskar donned the hat he promoted Shastri up the order to be promptly pulled down by Kapil again. Coincidence or intentional, one can only speculate about it.

Shastri eventually ended his career averaging 35 and 29 with the bat and 41 and 36 with the ball in Tests and LOIs respectively, after starting his career at number 10, modest numbers to say the least. However, he turned matches on their head and was a genuine match-winner, either with some quick fire runs or a dream spell of bowling.

#4 Steve Smith

Those who have started watching Steve Smith rather recently might be forgiven to believe he has always either a specialist batsman or a batting all-rounder. However, Smith began his career as a promising leg-spinner who could bat lower down the order, many down under even thought he was the next Shane Warne.

Smith was in the national side sooner than he would have imagined, more so in the shorter formats of the game, fast tracked for his ability to bowl loopy leg-spinners and the lack of quality spinners in the nation. His ice-cool head and ability to hold on to stunning catches did no harm to his case either.

However, though he made his entry into the international arena in 2009-10 on the basis of a career-best 7-64 playing for New South Wales. He had four centuries in the competition as well.

Smith started his international career at No. 7 in ODIs and 8 in Tests, selected as a frontline, genuine bowler in both cases. For the better part of two years, he was a bowler who could throw around his bat later in the innings.

However, when the Australians toured India in 2013, Smith was one of the few shinning lights in a rather humiliating whitewash, averaging over 40 in the two Tests he got a game in.

He has since cemented his spot in Test cricket, averaging above 38 in all the four series he has played since, three of them abroad. Smith played brilliantly when the Australians beat South Africa away from home, averaging 67.25 against the likes of Morkel, Steyn and Philander.

An attacking batsman by nature, it is perhaps a bit ironic that he has cemented his spot in Test matches as a specialist batsman and not so in the shorter versions.

However, his bowling has certainly been reduced to second fiddle now and plays as a speciaist for both, his national side and New South Wales.

#5 Sachin Tendulkar

Why does Tendulkar’s name come up in every list made on the planet? Yes, the Little Master with those big records wanted to be a fast bowler before deciding to rightfully concentrate on his batting. The very sight of the 5 ft 5 in diminutive lad come steaming up to the crease is a bit amusing. But with Tendulkar, you just never know. There is nothing on the cricket field he is not capable of.

With dreams of becoming a fast bowler, Tendulkar went to the MRF Pace Academy way back in 1987. But the great Dennis Lillee rejected his application and advised the Mumbaikar to concentrate on his batting instead. We all know what has transpired since that day till today, however, the following anecdote might not be a very well known one:

When Lilee was asked to recall what happened back then, he says rather sheepishly, “I actually feel very embarrassed because I rejected him as a fast bowler. I think I did him and the game of cricket a favour. I am just joking, but I will never forget (the incident).

"When he came back a year later he was just 15 years or so. I was there behind the nets. The first ball Sachin faced he hit it behind the bowler for a four. Sachin flicked the next ball for a four as well. The bowlers were not able to get Sachin and he was hitting them out of the park.

"When he was still batting with about 48 runs or so from 12 balls, I asked (the then head coach) TA Sekar who is this boy. Sekar laughed and replied you should know him, he is the boy whom you rejected when he wanted to become a fast bowler,"

#6 James Franklin

Franklin made his debut in the same series where Styris got his first promotion and batted at No. 10 in the first ODI. When Franklin burst on screen, he was a fast, lethally fast bowler capable of swinging the new ball well. However, he lost his place after the Sharjah Cup next year in 2002 after a string of poor performances.

The break meant he had time to work on himself and instead of focussing more on his primary skill, Franklin bolstered his batting technique and made it more tight and handy. After making his return a couple of years in 2004, he continued to bowl well and then hit his only century in International cricket – 122* at Cape Town against a testing South African attack.

Similar to Styris, a knee injury in 2006-07 meant he concentrated more on his batting than bowling. Though never a resounding success in International cricket, Franklin averages over 30 in Twenty20 games, a tad more than AB de Villiers to put things into perspective. He hardly rolls his arm over anymore in any form of cricket anymore.

#7 Ravichandran Ashwin

Ashwin’s first taste of International youth cricket came in the U-17 national team where he played as a specialist opener. After a string of poor, poor scores, Ravi decided to try his luck in the lower middle-order but still failed to make a jolly good impact.

Acknowledging his shortcoming, Ashwin decided to try out as a fast bowler (apparently, Ashwin’s father was a seamer of some recognition, having played competitive cricket in his younger days). However, an injury (how many times have we said that) laid those aspirations to deep slumber.

"I bowled flat and got a lot of bounce on matting wickets, and it helped. I could retain my place in the state and league team because I could double up as an off-spinner. My batting had stagnated — I would play a lot of shots and get out impatiently.

"Then in an under-19 game against Andhra, I was picked ahead of a regular off-spinner and picked up four wickets in each innings. I got a bagful of wickets for the under-22 team that season and came into Ranji reckoning," Ashwin said to the Indian Express.

However, Ashwin has developed miles and miles from being a flat bowler and though the fact that he is India's best spinner remains debatable, there is no questioning the fact that he has proved to be close to unplayable in India.

It is indeed true that once your place in the side is assured, your 'other' art befriends you sooner than later and Ashwin is a more than a decent lower-order batsman, at times being sent ahead of Ravindra Jadeja, who apparently is the only Indian with three first-class triple centuries to his name. In fact, it puts him at par with legends such as WG Grace, Bill Ponsford, Don Bradman, Wally Hammond, Graeme Hick, Brian Lara and Michael Hussey, but this, is a discussion for another day.

#8 Wilfred Rhodes

Wilfred Rhodes’ career begins way back in 19th century. Starting out in 1898, he broke into the English side as early as 1899 on the back of a brilliant debut season with his prolific left-arm spin, accounting for 154 English wickets at less than 15 apiece. He was hardly 21 then.

It is impossible to say with certainty whether it was Yorkshire or Rhodes himself who did not know of his ability to bat, but for four years, he did not know what it was like batting above number 10 for the English national side.

Indeed, the English side was filled with all-rounders, But Rhodes was never known to be a very good batsman in his stint either with Yorkshire or England, having scored only one double-digit international score in 11 innings. The counter-argument that he was not out in 7 of these is perfectly valid, but fact remains he was not promoted up the order despite some of these ‘all-rounders’ not having a really great time.

Though Rhodes may not have impressed in the net sessions as much, he gave a mighty fine display of batting in the first Test at the SCG in 1903, combining with Tip Foster to record the then highest 10th wicket partnership of all time – 130. His share in the score was 40*

One thing lead to another and soon, eight years later he was involved in the highest first wicket partnership back then, adding 323 with the legendary Jack Hobbs. In the same tour, his contribution with the ball was a mere 18 overs.

After not bowling for almost 9 years, he started out again, and bowled as if he’d never stopped. His return as a bowler saw him pick 164 wickets, averaging 14.42, the best of the season.

From a specialist bowler to a specialist batsman to an all-rounder, Wilfred Rhodes finished with close to 40,000 career runs and 4204 wickets, spread across 31 years of international and domestic cricket. His tally of 4204 wickets is certain to last the test of time. Of course due to the fact that the “time of test” remains uncertain.

No one in cricket can say ‘been there, done that’ as calmly as the inhuman Wilfred Rhodes.

#9 Anil Kumble

Anil Kumble, India’s most prolific bowler, accounting for over 600 scalps in Test cricket was chiefly a fast bowler in his formative years. However, when he was nearly 15 his elder brother coupled with another reason mentioned below persuaded him to switch to leg spin.

Kumble later recalled he learnt the art of leg spin purely on his own and there was no one to coach him with the technicalities and privileges of the art. However, he had the determination and talent to make it to the top which he did in style a few years later.

"When I started as a 13-year-old as a fast bowler, I was told to stop by my senior colleagues because they felt that I was bending my arm as a fast bowler. There was no television, no video then so they said you should not be bowling that way because that came natural to me so immediately I changed to bowling leg-spin," recalled Kumble, whilst talking about the rampant chucking in international cricket.

Though Kumble always was a ‘leg spinner’ on the scoresheet, he will fondly be remembered in the hearts of many Indian cricket fans as a fast medium bowler. Hardly a huge spinner of the ball, Jumbo relied on gravity defying bounce and pace variation for his wickets, traits you would naturally find in a seamer. As long as he was there, you would rarely see the tail-enders score more than a few runs, mopping them off in double quick time more often than not.

#10 Kevin Pietersen

Ironically, the person who coined the term “pie-chucker” himself started off as an offspinner who could bat a bit.

Very early in his career Kelves had a premonition of sorts when he moved to England for a 5-month stint as the overseas player for the Cannock Cricket Club. Very interestingly, this was not his only premonition as, by his own admission, he had a horrible time, specially with "those horrible Black Country accents”, living in a single room above the squash court and working part time at the club bar.

". . . a young off-spinning opponent of ours walked into the England dressing room after taking a few wickets for KwaZulu Natal in a tour match in Durban and plonked himself down next to me, asking if I knew of any English teams he could play for. I thought he meant club cricket and almost gave him my brother's number and told him to try Fives and Heronians (a local Essex cricekt club) but it turned out he had bigger ambitions than that..”

Nasser Hussain had this to say of KP, after he impressed in the game against England in 1999 playing for the South African domestic team.

Pietersen, batting at number 9 in that game scored a wonderful 61* studded with four fours and as many sixes. However, what really impressed Nasser was his off-spin bowling.

The stylish South African accounted for four scalps in the following innings, which included the wickets of Mike Atherton, Hussain himself and Michael Vaughan, all former English captains.

It is downright funny to hear KP say these words during the match, "I tried to bowl one length and vary my flight. The key was to try and contain the batsmen and tempt them into playing rash shots", for he did something exactly of the sort to bowlers all round the world to breathtaking effect.

A lack of bowling opportunities for his English County meant he concentrated more on his batting and how he ended his international career (assuming there will not be another sensational comeback) is really not something that needs to be stated, but one can only thank the stars the switch was made sooner than later or else we would have missed one of the finest displays of dominant and aggressive batting in the modern era.

Brand-new app in a brand-new avatar! Download CricRocket for fast cricket scores, rocket flicks, super notifications and much more! 🚀☄️