In his 25 years at Manchester United, Sir Alex Ferguson has created three undoubtedly great teams – the double-winning side of 1994, the treble-winning side of 1999, and the domestic and European cup winning team of 2008. One of the main differences in the more recent versions of the United team, and the earlier ones has been the change in the role of the central midfield. The 1994 team had powerful box-to-box midfielders in Bryan Robson, Paul Ince, and Roy Keane. The 1999 team had Nicky Butt and Paul Scholes in addition to Keane. Scholes, of course, was more of an attacking midfielder in the 1999 vintage, with Keane’s dynamism and energy liberating him to join up with United attacks. The job of midfielders in those United teams could be summarized best by whatPaul Scholes said to the Observer in 2011:

I always feel that if you’ve got two in midfield and one goes forward the other one stays, it’s as simple as that. – Paul Scholes

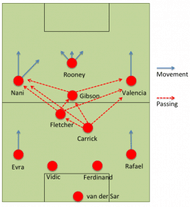

The post-2006 version of the Manchester United team, though, saw a different role for its midfielders. In this team, most of United’s attacking threat came from interchanging play between two United forwards, and the wingers. With the 2008 vintage team led by Cristiano Ronaldo and Wayne Rooney, United always had four attackers (Rooney, Tevez, Ronaldo, and Giggs/Nani) who could dovetail beautifully. Their speed, and fluidity of movement made it very difficult for defenders to mark them and nullify their attacking threat. In such a team, where the four interchanging attackers were so effective, the job of the midfield (comprised mostly of Carrick and Scholes) in the Premier League was one of two: to switch play rapidly to the wing, allowing Ronaldo and Giggs/Nani to take on the defenders; or to move the ball vertically to the forward in the hole (Rooney/Tevez). In Europe, where possession is key, having two skilled pass-masters as Scholes and Carrick allowed United to retain possession while also accomplishing the tactic of liberating the four players in attack. In terms of the midfield’s defensive responsibilities, the greater focus on possession reduced the need to rely on a ball-playing midfielder so much, and whatever Scholes and Carrick offered in terms of breaking up play was sufficient against most teams, especially with the abundance of riches in attack.

Things changed with the departure of Ronaldo and Tevez in 2009, as United ended up in more of a doughnut formation. The link-up between Berbatov and Rooney never really worked, with Berbatov’s lack of movement and speed often hindering United’s attacking tempo. In 2009-10 when Rooney had his 34-goal season and often played as United’s central striker in a 4-5-1/4-3-3 formation, United’s pattern of play involved a switch of play to the wingers (Nani/Valencia) as soon as the midfield got possession, and a reliance on Rooney to put away the crosses from the wings. With Rooney playing as the focal point of United’s attack, United lost the vertical channel that was earlier open due to Rooney/Tevez dropping into the hole. This created a rather one-dimensional attack, which a lot of powerful, big teams (Blackburn, Chelsea, etc.) could nullify. The three in midfield did give more solidity to the United midfield, helping the team deal with dynamic midfielders in the opposition. But it also tended to rely too much on Rooney’s energy to plough the lone furrow up front; and this over-reliance on Rooney clearly affected the team adversely, when Rooney was injured in the title run-in that season.

The situation was better for a while in the second half of the 2010-11 season, when Hernandez played as the lead striker, with Rooney in the hole. This shift enabled United to have an extra channel of attack which could originate from Rooney releasing Hernandez, who could use his speed while playing off the shoulder of the last defender. However, having two forwards implied the presence of only two central midfielders in the team, and United often found themselves outnumbered in the middle of the park. Scholes’ presence in the side tended to alleviate this problem, because of his ability to hold on to the ball, and find pinpoint passes, even from tight angles. However, against stronger teams, United had a lot of trouble in getting hold of the game in midfield, especially since Rooney lacked the discipline to drop back and help out his midfield defensively. Nowhere was this highlighted more than the 2011 Champions League final, where the Barcelona quartet of Iniesta, Xavi, Busquets, and Messi played their way merrily around Carrick and Giggs.

The dawn of the 2011-12 season initially saw a return to United’s old 4-4-1-1, where one central midfielder drove on ahead in support of the attackers, while the other stayed deep to shield the defense. Tom Cleverley and Anderson dovetailed beautifully in the first few games to accomplish this, as United began the season with a goal-glut. However, as Cleverley got injured, and Anderson suffered injuries/a loss of form, the team reverted to Carrick and/or Giggs/Fletcher in midfield. In Europe, the lack of pace for these pairings was brutally exposed, as United struggled to contain the high-tempo passing and dynamic movement from Benfica and Basel, and consequently crashed out of the Champions League in the group stages.

With Scholes’ return from retirement in January 2012, Scholes and Carrick once again, became the preferred midfield pairing. The return to the old possession-centric Scholes/Carrick pairing did yield dividends to United, as they embarked on their winning streak in the Premier League. But with this pairing, United once again reverted to something akin to their doughnut formation from 2009-10. This time, Carrick and Scholes played even deeper, to compensate for their lack of pace. This left a pretty big gap between Rooney in the hole and the midfield, which meant that Rooney often had to drop deeper than the attacking third to exert his influence on the game. The burden of both scoring goals and creating chances seemed to weigh heavily on Rooney, and eat into his effectiveness as the fulcrum of United’s attacks. In addition, a team could effectively play around the midfield two by playing between the lines, and stringing together passes at a high tempo. It was evident from the games towards the end of the last campaign and also from their European performances, especially against Athletic Bilbao, Ajax, Manchester City, and Wigan that United desperately needed some steel in their midfield, since the drop in mobility of both Carrick and Scholes left them vulnerable defensively.

The current season has seen United switch personnel with Kagawa now playing in the hole, with van Persie playing ahead of him as the lead striker. However, they have (by and large) stuck to the same defensive system that they followed last season. Carrick seems to be the first-choice midfielder, while Scholes/Cleverley have alternated roles as the second midfielder. However, the lack of mobility in midfield, as well as the missing ball-winning midfielder, has caused United problems in most of their games so far – against Everton, Southampton, Fulham, and Galatasaray. The performance of Yaya Toure last season, as well as those of Marouane Fellaini and Moussa Dembele provides further evidence for the same point. The situation hasn’t been helped by the constantly changing defence, which has been ravaged by injury. With the whole of the footballing fraternity now aware of these obvious defensive limitations of the United midfield, one can expect more teams to try and replicate the attacking patterns of play of Everton, Fulham, and Southampton to try and beat United.

So, what can United do in this backdrop, with Sir Alex Ferguson’s reluctance to buy a ball-winning midfielder? Well, for one, one can expect the timid, compact formation United tried to play against Liverpool against the bigger teams, which would rely on swift counter-attacks to score. The downside of this approach is that United really need to be on top of their game to get anything from those matches – something that they got away with at Anfield, despite playing so horribly. The other possibility is the return of Fletcher/Anderson to the side. Darren Fletcher is probably United’s only remaining box-to-box midfielder (assuming that he remains fit), and this was again in evidence during his performance against Newcastle in the League Cup. Alternatively, Anderson could do the job, but only if he is fit (which is rare) and up for the challenge (which is even rarer). If Sir Alex could get good, consistent performances out of one of these two midfielders, and pair them up with one of Carrick, Scholes, or Cleverley, it will go a long way to resolving our midfield conundrum. A third option, of course, is to dip into the transfer market in January, and buy someone like Strootman, or Héctor Herrera.

In terms of offense though, United seem to have succeeded in addressing the one-dimensionality of their doughnut formation. The big difference in this regard has been the presence of Shinji Kagawa in the hole. Kagawa’s ability to play between the lines, as well as his tendency to play short, quick passes and carefully weighted through balls (for example, his pass for Carrick against Galatasaray) means United have now got their most credible threat through the centre since the Rooney-Tevez combination in 2008. As a result, along with either wing, United can now effectively mount attacks even through the centre. This was especially apparent during the first half against Galatasaray, where Kagawa’s movement and his linkup with Carrick and Nani were a constant threat to the Turkish team. Furthermore, Kagawa’s presence also frees up Wayne Rooney from having to be both scorer and creator of the majority of United’s goals, which might actually help Rooney contribute more to the United cause. In addition, Kagawa is much more disciplined in his pressing and marking than Rooney, and once integrated completely into the side, he could do a more effective job in helping out the midfield defensively, especially in tracking runs of opposition players from deep.

To summarize, the role of Manchester United’s central midfielders has evolved over time, and a lack of freshness in the lineup (Fergie hasn’t bought a central midfielder since the summer of 2008, when Anderson and Hargreaves arrived) has allowed flaws to creep in, into the way our midfield operates. The way Sir Alex addresses these flaws, and the manner in which the midfield plays around their obvious limitations, might well decide how much success United achieve this season.