"I give you my word that we will put in an effort. I don't know if we'll win, but we'll persist. Put on your seat belts, because we're going to have fun."

Two trophy-less seasons had passed at the Nou Camp when ‘Pep’ Guardiola was appointed manager of FC Barcelona ahead of the 2008/09 season; the above were his words during his presentation to the fans. He was tasked with resurrecting the fortunes of one of the most famous European clubs in football and bringing back the glory days to Catalonia.

Six full seasons on, he stands out as one of the best managers in world football, the reputation of both Barcelona and his own personal brand greatly enhanced.

The name Guardiola does not merely represent a man any more; it has come to represent a faith, a belief, a philosophy; one that has delivered success on a consistent basis at the highest level. Whether you love his tactics or hate them, there is no disputing the fact that ‘talking tactics’ and ‘formation fiddling’ just went up to a whole new level with his coaching in play. And if there’s one word that would aptly sum up all of Guardiola’s coaching adventures so far, it would be ‘dynamism’.

With Europe’s top leagues on hold due to the international break, it’s a good time to take a look at the evolution of Pep’s formations from Barcelona to Bayern Munich. For ever so quietly, away from the main stories making the rounds in the continent, Guardiola’s Bayern have made another impressive start and are looking the best amongst all the reigning league champions. That’s not all; Guardiola has thrown in another new tweak in the Bavarian giants’ strategy, which has been quite fascinating.

Pep’s Barcelona and the 4-3-3

Even before we get to talking about the actual formations, I think it is essential that we fully recognize Pep’s philosophy – the philosophy to build teams on the foundations of unison, work rate, patience, ball movement, zonal play, positional play and finally dynamism, both in formations as well as personnel. Each of Guardiola’s acquisitions was done with a specific goal in mind.

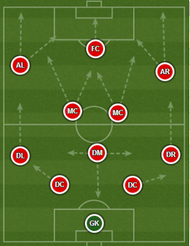

In his all-conquering first season, when Barcelona won the treble, Guardiola operated predominantly with a 4-3-3 formation. While many critics believe that all he did was put together a group of some of the most talented players around, that is not necessarily true. Guardiola had a plan and a reason for putting in each of the players that he inserted regularly into his line-ups.

Holding possession by moving the ball both laterally and forward with crisp, short passes was the principle that they religiously stuck to. And they would wait for their opportunities when the opposing defence would get unhinged to strike the final blow. This early version though played slightly quicker, largely due to the presence of forwards Thierry Henry, who played wide left, Samuel Eto’o, who played through the middle, and Lionel Messi, who started wide right.

Behind that trio was Sergio Busquets, promoted from the B team, in the holding role, with Xavi and Andres Iniesta to his right and left respectively. Eto’o at the time was at the height of his powers, while Messi had still not reached his magical peak yet. So utilizing the pace and power of Henry and Eto’o, while relying on Messi’s ability to dribble and draw defenders, was essential.

Xavi played behind the front three as the deep-lying playmaker and Busquets played the roles of anchor-man and Xavi’s wingman, always moving with him, protecting him from opposing defenders and acting as a foil to receive and spray passes. He was also the added cover for the backline, slotting in for one of the centre-backs, notably Gerard Pique, whenever he ventured forward.

Iniesta would venture further forward as the advanced playmaker, either going central to support the forward trio or taking up the space out wide vacated by Henry or Messi. This also required a very hard-working central striker and Eto’o did just that, sometimes falling back to receive the ball and actually allowing Henry and Messi to work as a front two.

Subsequently, Guardiola converted Messi into a full-fledged striker from a winger, and Eto’o and Henry would depart. Zlatan Ibrahimovic was bought in as Guardiola wanted to find a different way of scoring goals, but that experiment didn’t go very well and he used him sparingly.

This was when the triangle offense really came into its own, as Barca’s players would move forward with the ball, triangulating their passing with almost geometric precision to unseat teams. Can you believe that 2008-09 was the last time that Messi scored less than 49 goals in all competitions?

David Villa would take up Henry’s role out wide on the left after the Frenchman’s departure, and Pedro would take up the wide right position. However, Pedro wasn’t a regular in the team and Guardiola would go quite a few games with Iniesta/Villa/Messi as the front three.

Then came the acquisition of Cesc Fabregas and the introduction of the false nine concept. With Fabregas and also Alexis Sanchez in the side, Guardiola had a new level of freedom and dexterity with which to operate. Both Fabregas and Sanchez could play in a multitude of positions, which is why they were bought. Fabregas enabled Pep to play the striker-less formations, the conventional 4-4-2 with Messi and Pedro/Sanchez up front, and the 4-1-3-2 with him playing in a midfield three with Iniesta and Xavi and Pedro, and Sanchez either side of Messi up front.

Defensively, Alves would bomb forward on the right with Puyol covering for him. That would result in Abidal falling back into the left side of a back three, with Pique and Puyol. Also, the long balls were sparingly employed by Pep’s Barca sides as they lacked the height and physicality up front and also because their defenders were more comfortable playing the ball out on the ground as Pique continuously did. Pique’s forays forward also meant a covering job for Busquets to drop back and aid Puyol and Abidal.

Throughout his time at Barca, there were two players outside of Messi that were of utmost importance to make the formation work and make it dynamic – Alves and Abidal.

Alves was key in the attacking areas of the right flank. His intricate interchanges with Messi in the opposition half were among Barcelona’s biggest threats. When Messi moved into the middle as a false nine, Alves continued to play high up the pitch, importantly stretching the play, especially since both Villa and Pedro too were more inclined to move in from out wide.

Alves’ ability to go up and down so regularly and with such frightening results made up for the lack of a right winger or right midfielder. His forward menace also managed to keep the opposition left-back pinned down in his own half.

Abidal was hugely important in compensating for Alves. He would push forward when necessary, but his ability to sense danger and drop deep to operate as an additional third centre-back when required were irreplaceable. He also covered for Busquets and Pique in their respective roles whenever Barca were in pursuit of a goal and pushed more bodies forward. Abidal was the guy who made the formation tick at the back with his amazing ability to play left-back, centre-back and defensive midfield to perfection.

All in all, Guardiola’s formula at Barca for much of his stay was built on the full-backs, dribbling centre-backs, the wide forwards who would dart in and the midfield duo of Iniesta and Xavi and later the concept of the ‘false forward’.

Bayern 1.0 – Beginnings with 4-1-4-1

German giants Bayern Munich came calling for Guardiola’s services and he agreed to take over the reins from the 2013-14 season onwards in what was a tough act to follow as his predecessor Jupp Heynckes signed off in some style leading the Bavarians to a historic treble with a team that was devastatingly destructive.

Bayern 1.0 saw Guardiola employ a 4-1-4-1 formation. This formation was built to explore Bayern’s depth in midfield especially around the ability of Toni Kroos to distribute, move up and down the middle of the pitch and also play as a playmaker. While at Barca, Guardiola had players of short stature at his disposal who were very good in possession; at Bayern he had more direct players in the likes of Thomas Müller, Arjen Robben and Franck Ribery and he tried to cater to their strengths by banking on the influential Kroos.

Philip Lahm, possibly the best right-back in the world was given a new role by Guardiola as a holding midfielder breaking up the erstwhile duo of Bastian Schweinsteiger and Javi Martinez that his predecessor used to telling effect. His need for a more mobile holding player with good passing range saw him make the shift and that meant Rafinha would take Lahm’s place at right-back.

However, the full-backs under this system were part of a mobile triumvirate that would move up and down with Lahm and would more often than not join up with the two central midfielders to make a four in the middle occupying the space vacated by the two wingers who’ve joined up in attack. The use of ‘false full-backs’ was made possible by the presence of Ribery and Robben, who provided the width with their forays out wide to reduce the necessity for advanced full-backs. In the absence of one or both, Alaba and Rafinha tended to play in a more traditional full-back role.

And it was that versatility that got them off to such a flying start last season, eventually helping them win the Bundesliga at a canter. Opposing teams simply could not handle the many different attacking formations in the form of an attacking double-pivot of either Götze/Robben, Götze/Müller or Müller/Robben. Also, unlike at Barca, this Guardiola team played a good number of good long balls because – a. their defenders weren’t the dribbly kind like Pique and b. the presence of aerially gifted players such as Müller and Mario Mandzukic.

The presence of multiple playmakers ensured that they could swap roles freely and the ones not on the ball could then run the channels effectively, complementarily opening up space for each other to operate in.

The overlying emphasis of this formation was to always have three central midfielders on the pitch at any point of time. That’s why Pep went out and bought Thiago Alcantara, not for old time’s sake. Lahm explained as much in an interview last year:

The attacking pivots also helped in pressing from the front and while not as intense and harrying as they were under Heynckes, Bayern were still very effective doing their version of the Barca press to dispossess opponents.

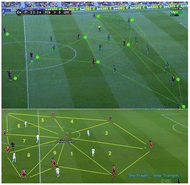

This formation was another continuation in the triangle system of Guardiola, except that instead of widening the pitch to stretch the defence like at Barca, here the system was about overloading the centre of the park with triangles formed all around the centremost midfielder, usually either Kroos, Lahm or Schweinsteiger.

And this system also kept up the bargain of tactical flexibility for Guardiola as it could morph into a 3-4-1-2, 4-4-2, 4-3-3, even a 2-4-4 at times if chasing a game.

The 4-1-4-1 for all its tactical nuances had some weaknesses. It involved the full-backs playing almost as midfielders and with Lahm’s solidity no longer present at right-back, it exposed Bayern, who played a high defensive line, to individual mistakes and long passes. And as brilliant a sweeper-keeper as Manuel Neuer is, he could not always save the day for them, especially against quality opposition.

When used ineffectively the overload of playmakers in the centre muddled the midfield and made their attack look toothless and the build-up slow. Also, they could almost never capitalize on quick counter-attacking opportunities.

All of this came to a head in their semi-final tie against Real Madrid in last year’s UEFA Champions League. Madrid were a side perfectly built to expose each and every flaw of this system and it was a matchup nightmare for the German side. A front six of Cristiano Ronaldo, Karim Benzema, Gareth Bale, Angel di Maria, Luka Modric and Xabi Alonso had too much pace, power, and on-ball ability to be contained by the 4-1-4-1. Ronaldo and Bale ran roughshod over the two ‘false full-backs’ and Benzema’s movement in combination with one of the two plus di Maria took the two centre-backs out of the equation as well.

Also a few players such as Mandzukic suffered as he was forced to make runs out wide and become a provider at times instead of a goal threat and that saw him lose his starting spot to a midfielder with Guardiola preferring to play Müller as the lone striker instead. Ribery and Robben were forced to make the unnatural shift to receiving the ball and quickly giving it back, instead of venturing forward to take on the defenders which took the destructive nature out of Bayern’s attacks.

Bayern 2.0 – A 3-4-3

With all that had gone by and seeing the limitations that the 4-1-4-1 caused, Guardiola introduced a 3-4-3 system against Borussia Dortmund in the DFB Pokal final of last year to redeem himself after the chastening defeat to Madrid. And he has continued with it this season.

The 3-man backline sacrifices width for numerical superiority in dealing with opposing attackers while providing a man advantage in midfield.

In defence, it relies on the 3-man backline and the 4-man midfield, which includes the two wingbacks. And in attack, the formation moulds into a 3-4-1-2 or 3-4-2-1 using either one attacking midfielder (Götze/Kroos) behind two strikers (Mandzukic/Robben and Müller) or two attacking midfielders (Kroos/Müller, Kroos/Götze) and the lone striker (Robben/Müller/Mandzukic).

The 3-4-2-1 has been the one that Bayern have gone with more often and it is a very demanding formation. The two withdrawn strikers or attacking mids play a critical role as they alternate between shifting wide or tucking in behind the main striker. Due to only one striker up top and a lack of wingers, the role of the wingbacks becomes more important. Without their inputs, Bayern can't maintain their superiority when attacking. While being aggressive though, they have to remain disciplined, as they are the sole defensive cover on the wings. So even one slip-up can be costly.

However, the 3-man backline does provide an extra target against teams whose forwards press hard, like Dortmund. The extra man enables them to pass the ball out smoother. The central centre-back often functions as a key distributor, much like Pique did at Barca while the two guys either side of him push wide almost in a full-back-like position to use and cover the space.

Someone like Javi Martinez and Holger Badstuber, both of whom have played as defensive midfielders, can play centre-back better in this formation as it helps them break up play, even at the cost of leaving their position thanks to added protection from the sides and also helps in their distribution. If need be they can even step in to join the midfield to provide extra impetus in attack as the other two centre-backs would then converge to form a back-two.

Till now, Guardiola has used six different players in the full-back roles this season – Pierre Hoijberg, Juan Bernat, Philip Lahm, David Alaba, Rafinha and Sebastian Rode. Each of them offers him something different; Bernat is more of a traditional full-back and more or less parks himself along the touchline; Alaba and Rafinha are capable of not just playing as full-backs, but also tucking into midfield while Rode and Hoijberg are more inclined to drop inwards as defensive midfielders.

Depending on what weakness a certain opponent has and what he wants to guard against regards his own team, Guardiola can pick his personnel. To top that, you have Lahm, who can play any of those positions on either side. And hence the dynamic fluidity of the wingbacks will be something to look forward to this season.

Each has its own by-product too. Rafinha and Bernat playing generally means they will stay wide to stretch defences providing space for the holding midfielder(s) and centre-backs to join in the attacks; when Alaba and Lahm play, they can go either way, bombing forward in attack or cutting in allowing the likes of Götze, Robben, Ribery and Shaqiri to go wide.

The acquisition of Xabi Alonso has also greatly aided this formation as he acts as a defensive cover, partnering Lahm and due to his long-ball ability can support the attack without ceding his position from deep. Perhaps that’s why they went for him over Sami Khedira. He also drops in as auxiliary centre-back for Jerome Boateng whenever necessary. Mehdi Benatia’s arrival has also bolstered the defensive ranks.

The system also helps for the cover of Kroos with Alonso now playing Lahm’s role from last year allowing the captain to operate further up the pitch in the right side of a diamond with Alonso bottom, Alaba left and Götze at the tip. It will get even better when Thiago returns from injury for he brings with him an added dimension where he can play double-pivot with Lahm (as Kroos did last year).

There’s also Robert Lewandowski at his disposal this year. He finally has the dynamic possession-based striker he's always wanted. The mobility the Pole brings into that frontline allows Pep to use different combinations of attacking midfielders behind him. Lewandowski can play as a false 9, play wide by interchanging with the wide players and can even drop deep when needed. Götze and Müller augmenting the Pole makes for a very creative frontline. It also allows him to switch from two midfielders and a striker to one midfielder and two strikers (Müller joining Lewandowski) fluidly during a game.

This formation like the 4-1-4-1 last year can also seamlessly morph into a 4-2-3-1 or a 4-3-3, a 3-5-2, or even a 3-2-2-3 (as against Manchester United in the Champions League last year) as the situation demands.

Another tweak and the 3-3-3-1

We have also seen Bayern operate in a 3-3-3-1 in a couple of games where three clear lines of three (defenders, holding mids, attacking mids) stack up on top of each other with a lone forward up front. At home to Stuttgart in the third game of their Bundesliga campaign, Bayern started with Badstuber-Dante-Boateng in a 3-man backline. On top of them stood Bernat, Alonso and Lahm. They opted for this rigid defensive setup as a base on which to work from.

Boateng would often pull wide and operate almost as a full-back in support of Lahm and Müller ahead of him. Lahm would play a box-to-box role, another feather in the career of this remarkable footballer. Bernat played as a left winger almost when in possession, but would drop back in front of Badstuber and alongside Alonso when defending. If either of Dante or Boateng got drawn out wide on the right, Badstuber would deputise in their positions and Bernat would drop further back to take Badstuber’s place. Conversely if Badstuber got drawn out wide left, Bernat would stay up allowing Alonso to drop back and take Badstuber’s place who would now be wide left. If anything came through the middle, they fell back to their original 3-3-3-1 and stuffed them out.

The forward line played according to the movements of Müller. When the German went wide right, Lahm would step into his attacking role while Boateng would support him on the flanks. If he moved up to support Lewandowski, Lahm would go right to provide width and again would be supported by Boateng. Accordingly, Götze would do the same, either slipping in behind the two strikers to form a diamond or go wide left.

Evolution based on adjustments and experiments

As we’ve covered the various formations there are a few things that become very evident as core characteristics of any formation that Guardiola deploys:

- Possession

- Constant and fluid adjustments during a game

- Attacking and defending as a unit

- Coordinated positional play

- A fetish for multi-skilled and multi-positional players

For the vast majority of the time, his formations and their underlying ethos have served his teams brilliantly. On the rare occasion, they have been trumped by strong teams with tactically astute managers and players built to tackle a Guardiola team.

At Barcelona, they were at times too one-dimensional and teams would ‘park the bus’ to snuff them out and hit them on the counter to emerge victorious. The form of Pique and Puyol also tapered towards the end of his reign which made Barca more susceptible to opposition attacks, the defence being an area he did not address.

Upon his arrival at Bayern, many predicted he would imbibe the tiki-taka system there too, but he didn’t (not entirely) choosing to work around the strengths of the players present in the team. But his 4-1-4-1 formation, despite offering much flexibility, had a soft underbelly and was exposed as last season wore on and this year, in recognition of that, he has made another alteration.

The jury is still out on the two new systems, but one thing is for sure, the pace has quickened up considerably; the build-up is not as slow as what it was last year and the new formation allows for greater gamut of changes through one single game as seen against Manchester City in their Champions League opener where Alaba went from playing left centre-back in a back-three, to left wingback to the left of a midfield diamond in the space of about 45 minutes.

Also, Götze has gotten a greater role (Iniesta’s role) and is the leading scorer overall for the club with 5 goals which tells a story in itself. The presence of Lewandowski has accentuated the talents of his midfielders.

As always, Guardiola is thinking, scheming and looking to constantly adjust his team so that they don’t become predictable. He learns from his previous experiments, reinforces what worked while reanalysing the elements that didn’t (like Schweinsteiger not working well in his fluid formations and encouraging Lahm to play a box-to-box role this year) and tweaking them.

From now to the end of the season, we may yet see more new tactics and formations from the Spaniard’s box. After all, the man has re-defined formations and brought about a true evolution in that domain like never seen before.